Anti Ku Klux Klan protesters marched in Philadelphia on 5 November, 1988, after white supremacist groups agreed to call off a rally that would have been held the same day. Picture by Lori Schaull

‘Anti-Blackness’ refers to a pervasive and deeply entrenched form of dehumanisation and exclusion targeting people racialised as ‘Black’, particularly those of African, Afro-diasporic, and Australasian descent. While often categorised under the broader umbrella of ‘racism’, some scholars argue that anti-Blackness constitutes a distinct formation rooted in the histories of the Atlantic slave trade and European colonial domination. Globally, it manifests in structural inequalities and in the everyday experiences of communities shaped by the afterlives of slavery.

Anthropology has historically been complicit in producing and legitimising anti-Black ideologies—constructing Blackness as inferior or subhuman while centring a fictive white ideal. Yet, anti-racist anthropologists have long challenged these paradigms, exposing their role in sustaining racial hierarchies. Today, anti-Blackness continues to shape disparities in healthcare, housing, education, incarceration, and cultural representation. At the same time, anthropology’s theories and methods—especially ethnography—offer tools to document, analyse, and challenge anti-Blackness in everyday life. This entry traces the discipline’s entanglement with anti-Blackness, emphasising both its role in reinforcing racial domination and its potential as a critical site for resistance, repair, and reimagining justice.

Introduction

Anti-Blackness is a global structure of domination that positions Blackness as a threat, a problem, or a deficit. It operates through and encompasses a wide range of practices and systems—including violence, exclusion, exploitation, and neglect—that have targeted people of African and Australasian descent across time and place. Though often discussed under the broader umbrella of ‘racism’, anti-Blackness constitutes a distinct formation: it has been foundational to the development of colonial empires, modern capitalism, and liberal democratic institutions (Wilderson 2010; Vargas 2018; Allen and Jobson 2016). Anti-Blackness shapes policing practices, incarceration, and economic deprivation, but also standards of beauty, moral hierarchies, and social relations in everyday life. From the commodification of enslaved people to the surveillance of Black life, anti-Blackness remains central to the organisation of the modern world.

Anthropology has played a contradictory role in relation to anti-Blackness. As a discipline, it has contributed to racial classification, legitimised colonial domination, and excluded Black scholars from its intellectual traditions (Harrison 1992; Mullings 2005). Yet anthropology’s core methods—especially participant observation and ethnographic attention to lived experience—also offer tools for understanding how anti-Black structures are produced, contested, and navigated in everyday life. This entry explores that tension. It traces how anthropology has both reinforced and challenged anti-Black ideas, drawing from Black feminist theory, critical race studies, and decolonial ethnography to highlight how Black communities generate practices of endurance, resistance, care, and worldmaking.

Within white supremacist thought, African and Australasian Blackness has long symbolised radical alterity—a condition imagined as incompatible with civilisation, reason, or beauty (Davis et al. [1941] 2022; Smedley 1993). In this racial schema, Black people were often cast as subhuman, or as existing outside the category of the human altogether (Douglass 1854; Fanon 1952; Jung and Vargas 2021; Weheliye 2014; Wilderson 2020). These ideas were not merely ideological—they were embedded in laws, institutions, languages, and cultural norms around the world (Hall 1997; Morgan 2002; Spears 2021).[1]

Consider, for example, Jim Crow segregation laws in the United States. This body of legislation, introduced between roughly 1877 and 1967 and predominantly across the US South, restricted the access of Black Americans to all major institutions of public life. It disenfranchised Black people politically, limited their economic possibilities, reduced their access to education, and supported a climate of anti-Black terror sustained by state officials and white militias. Anthropologists have argued that, under these laws,‘“Blackness” is the master-symbol of derogation in the society, and the “typical” Negro characteristics of dark skin color and of woolly or kinky hair are considered badges of subordinate status (Davis et al. [1941] 2022, 16). Such forms of anti-Blackness continue to shape institutions, economies, hierarchies, languages, desires, and intimacies in everyday life, even today.

This entry examines anti-Blackness in historical and contemporary perspective, showing how anthropologists and ethnographers have both enabled and challenged the racial orders that sustain white supremacy (Mullings 2005a; Beliso-De Jesús, Pierre and Rana 2025; Pierre 2020). Contemporary anthropologists draw on the Black radical tradition and interdisciplinary literatures on Black ontology (i.e. the study of what it means to exist as a Black person) and Afropessimism (i.e. the study of fundamental structural aspects of society that perpetuate anti-Black racism) to examine how anti-Black violence and stigma organise modern life and death (Fanon 1952; Sexton 2008; Vargas 2018; Wilderson 2020). While the social construction of race has been examined across disciplines, anthropology’s ethnographic methods allow for sustained attention to how anti-Blackness is lived, embodied, and resisted in everyday life.

Slavery and anti-Blackness

Slavery was not always synonymous with Blackness (Patterson 1983; Smedley 1998; West 2002). In antiquity and the medieval period, Blackness was often associated with symbolic or spiritual meaning, rather than biological inferiority. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus described Ethiopians as beautiful and noble; the fourteenth century Maghrebi intellectual Ibn Battuta praised the justice of West African Muslims; and medieval Europe venerated Black saints such as the Egyptian St. Maurice and the Black Madonna (Bindman and Gates 2010; Snowden 1970). Even when Blackness carried negative connotations, it was not yet biologically overdetermined and pathologised. The association of Blackness with heritable enslavement developed gradually through European colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade, as slavery became racialised in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Smedley 1998; Gates and Curran 2022).

By the nineteenth century, after centuries of institutionalised chattel slavery, i.e. a form of slavery where slaves are considered to be the ‘property’ of their ‘owners’, Blackness had become a symbol of perpetual bondage and degradation. To be Black in most Euro-colonial societies meant being marked by ‘social death’—alienated from kin, honour, history, and futurity (Patterson 1983; Trouillot 1995; Wilderson 2020). Early anthropologists and ethnologists—especially those associated with the ‘American School’, led by Samuel Morton, Josiah Nott, and Louis Agassiz—helped naturalise this association by grounding it in pseudoscientific theories of racial difference, transforming a historically contingent condition into an allegedly immutable ‘truth’ (Gould 1981; Painter 2010; Smedley 1993).

In the wake of slavery, Black life continues to be evaluated through a white supremacist gaze—simultaneously feared and exploited, always in relation to its utility for colonial-capitalist accumulation (Du Bois 1903; Robinson 1983; Sharpe 2016). This was the case in the late nineteenth century when recently freed American slaves and their offspring were kept in highly exploitative working conditions, constituting ‘a segregated and servile caste, with restricted rights and privileges’ (Du Bois 1935, 32). It continued in the twentieth century, when Black Americans served as a capitalist underclass both in the American industrial and service economies, but also in the privatised for-profit prison economy that relies disproportionately on Black labour (Gibson-Light 2023; Oshinsky 1996). And it persists today, as Black lives around the world continue to be considered largely disposable, whether they are Haitian emigrants seeking a better life or disadvantaged Black children in the favelas of Brazil being subjected to police abuse (Joseph and Louis 2022; Smith 2016). Anti-Blackness developed as a system of racial domination shaped by intersecting hierarchies of race, gender, class, religion, and ethnicity—privileging whiteness, and especially white men, above all (Baldwin and Mead 1971; Mullings 2005a; Shange 2019).

In the post-slavery world, Black bodies were recast as a ‘social problem’, requiring political and scientific intervention (Baker 1998; Du Bois 1898, 1903; Harrison 1992). In the US, this became the so-called ‘negro problem’; in the British Empire, the ‘native problem’. Both framed Black and Indigenous populations as inherently disorderly and unfit for self-rule—justifying ongoing racial domination. Anthropology was complicit in this global racial order. Emerging alongside imperial conquest, it helped classify, study, and govern the ‘savage’ or ‘primitive’ subject (Baker 1998; Blakey 2010; Smedley 1998; Trouillot 1991). As Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot observed, ‘the savage was the alter ego the West constructed for itself… the raison d’être of anthropology’ (1991, 28, 40).

Yet anthropology also became a space for critique and resistance. Black, Indigenous, and other minoritised scholars have used ethnographic tools to expose structures of racial domination and articulate alternative visions for humanity (Mullings 2005a; Harrison et al. 2018). Understanding anti-Blackness through anthropological and historical frameworks is vital to building an anti-racist, abolitionist, and decolonial anthropology (Bolles 2001; Cox et al. 2022; Harrison 1991; McClaurin 2001; Perry 2016).

Anti-Blackness and the colonial foundations of anthropology

To understand contemporary expressions of anti-Blackness, we must first trace its genealogy through European ‘Enlightenment’ thought. Central to Enlightenment philosophy was the presumption that Black and Indigenous peoples existed ‘without history’, outside the temporal and moral horizons of Western modernity (Fabian 1983; Fanon 1952; Hegel 1894; Trouillot 1995; West 2002; Wolf 1982). Racial difference was increasingly cast not only in cultural or religious terms but as a biological fact, justifying colonial conquest as a civilising mission. Anthropological knowledge, especially in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, became an instrument for racial surveillance and control. Black and Indigenous bodies were rendered as objects of study, classification, and debate, often in the service of slavery, settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and genocide. Thus, anthropology helped to uphold the normative distinction between ‘primitive’ and ‘civilised’ people and situated it along the colour line. In its studies of Black and Indigenous people, anthropology all too often ignored white rule and allowed anthropologists to serve as diplomats and public relations experts for white rule (Willis 1972; see also Baker 1998; Anderson 2019).

The modern scientific racism to which early anthropology contributed emerged alongside Enlightenment rationalism. Carl Linnaeus’s Systema naturae (10th ed., 1758) classified humans into continentally-bounded ‘varieties’. He described Africans as ‘Black, phlegmatic, lazy… sly, sluggish, neglectful’, and contrasted them with idealised Europeans, ‘governed by rites’. Relying on dubious colonial travel accounts, Linnaeus also claimed African women had ‘elongated labia’ and ‘breasts lactating profusely’.[2] These dehumanising descriptors shaped later anatomical and racial science, grounding anti-Blackness in the language of empirical objectivity and universal classification (West 2002; Moore, Kosek and Pandian 2003).

European theories of Black inferiority found fertile ground in the antebellum (1815-1861) United States. Thomas Jefferson—Founding Father, slaveholder, and third US president—substantially shaped American racial thought. In Notes on the state of Virginia (1781), he notoriously speculated: ‘I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks… are inferior to the whites in the endowments of both body and mind’ (222). This conjecture framed racial hierarchy as reasoned observation rather than prejudice, lending intellectual legitimacy to chattel slavery and segregation (Walker 1830; Chamberlain 1907; Finkelman 2014).[3] Jefferson’s views were not merely abstract. He enslaved over 700 people and exploited the reproductive capacities of African-descended women. His long-term relationship with Sally Hemings—an enslaved woman of mixed ancestry—produced several children, all of whom inherited enslaved status through their mother (Cohen 1969; Woodson 1918; Finkelman 2014).[4] This dynamic of sexual domination, denial of paternity, and commodification of Black life exemplified the intimate operations of anti-Blackness at the heart of American democracy.

Jefferson’s influence extended beyond the Monticello plantation in Virginia, which he owned, and even beyond the plantation system that dominated the economic development of the American South from the seventeenth until the twentieth century. As president, he severed trade relations with the newly independent Black republic of Haiti, fearing its revolutionary example would inspire slave uprisings across the Americas, and especially in the US South (James 1938; Scott 2004, 2014; Trouillot 1995). His statesmanship and racist writings laid the groundwork for the so-called ‘American School of Anthropology’ which codified pseudo-scientific racial theories and enshrined anti-Blackness in American science, law, and education (Chamberlain 1907; Finkelman 2014, 198).

While Jefferson laid the ideological foundation, the ‘American School’ formalised these ideas. Central was ‘polygenism’—the theory that racial groups like ‘Negroes’ and ‘Caucasians’ were biologically distinct species with immutable traits (Gould 1981; Keel 2013; Painter 2010). Polygenists claimed that Black people were naturally inferior and biologically suited for subjugation. Samuel G. Morton, often called the ‘father’ of American physical anthropology, used manipulated skull measurements to ‘prove’ that Africans ranked lowest in the human hierarchy (Stocking 1968; Smedley 1993; Blakey 2020). These claims helped justify slavery and segregation as the natural order (Morton 1839; Ralph 2012).

Closely linked was the theory of ‘hybrid sterility’, which pathologised racial mixing, and popularised the belief that ‘mulattoes’ were biologically unfit hybrids (Nott 1843). For example, an 1843 article in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, claimed: ‘[T]he mulattoes are intermediate in intelligence between whites and blacks… they are less capable of endurance and are shorter lived… the women are bad breeders and bad nurses… the two sexes when they intermarry are less prolific’ (Nott 1843, 29–30). From such claims, it was concluded that interracial reproduction should be prohibited. These arguments later informed eugenics (i.e. ideas about improving the biological makeup of humans through selective breeding) and anti-miscegenation laws, embedding anti-Blackness in US legal and scientific infrastructure (Hochschild and Powell 2008; Nobles 2000; Pascoe 2010).

Yet these theories were never uncontested. Black intellectuals like Frederick Douglass (1854; 1881) and Anténor Firmin (1885) repudiated scientific racism and established and defended the rights of Black people. Rather than accept white supremacist race science, they argued that differences among racialised groups stemmed from historical and environmental conditions—not biology (Allen and Jobson 2016; Drake and Baber 1990; Fleuhr-Lobban 2000). Similarly, theories of polygenism and hybrid sterility were attacked as fallacious by noted scholars who condemned white anthropologists for being ‘blinded by passion’ and relying on false ‘audacious paradoxes’ (Firmin 1885, 68). Against the myth of hybrid sterility, Firmin wrote: ‘The fecundity of mulattoes is a fact so well known… that one can only be surprised that a scientist… can question it’ (68). Despite these rebuttals, obsession with Black bodies and racial mixture continued to dominate anthropological debates into the twentieth century (Anderson 2019; Baker 2020). Nevertheless, the early vindicationists, as they were known, laid foundations for an anti-racist and decolonial anthropology—one that exposed race science as spurious ideology serving domination.

Although polygenism lost credibility by the late nineteenth century, Darwinian evolutionary theories did not end scientific racism. Racial hierarchies were rearticulated through social Darwinism and eugenics (Stocking 1968; Gould 1981; Dennis 1995). Darwin’s theory of common ancestry debunked polygenism but recast human difference as evolutionary hierarchy. In The descent of man, Charles Darwin wrote:

At some future period… the civilized races of man will almost certainly exterminate, and replace, the savage races… The break between man and his nearest allies will then be wider… between man in a more civilized state… and some ape as low as a baboon, instead of as now between the negro or Australian [Aboriginal] and the gorilla (1871, 156).

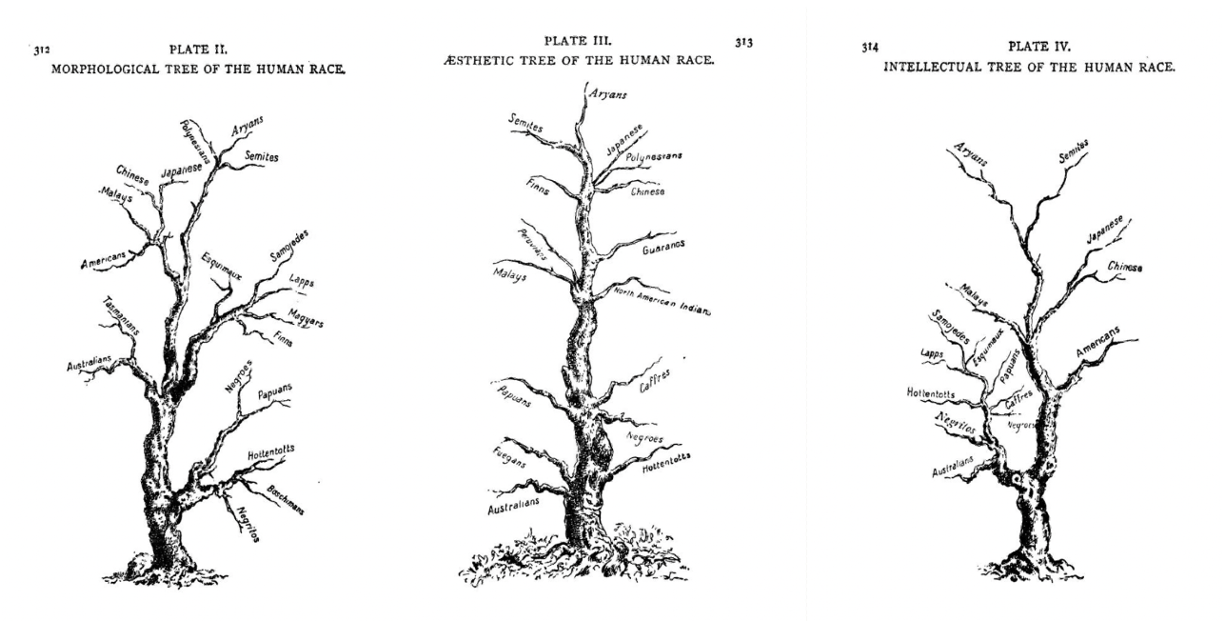

Such comparisons gave scientific credence to anti-Black and anti-Indigenous tropes, framing colonial violence as evolutionary progress. Social Darwinists like Herbert Spencer used these ideas to justify imperialism and capitalist inequality as inevitable (Dennis 1995; Magubane 2003). The rise of eugenics, a term and theory coined by Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton, reinforced this logic. Eugenicists envisioned humanity as a grand evolutionary tree, with elite Europeans at the top and Black and Indigenous peoples as stunted lower branches. These arboreal metaphors ‘naturalised’ racial hierarchies in society (Moore, Kosek and Pandian 2003).

In Europe, anthropologists also illustrated ‘morphological’, ‘aesthetic’, and ‘intellectual’ trees to represent and legitimise these imagined racial hierarchies (Mantegazza 1881; see Fig 1). In these hierarchies, ‘Hottentots’, ‘Bushmen’, ‘Negroes’, ‘Caffres’, ‘Papuans’, ‘Australians’, and ‘Negritos’ are placed at the bottom, and ‘Aryans’—white Europeans—at the top (Taylor and Marino 2019, 116–7). In short, social Darwinism replaced polygenism but not racism—it simply gave anti-Blackness new scientific language.

(Fig 1). Paulo Mantegazza’s “Morphological, aesthetic, and intellectual hierarchies of the human race.” (1881).

The Black body

Building on the racial typologies of polygenism and the biological determinism of social Darwinism, physical anthropologists and early social scientists increasingly turned their attention to the Black body as an object of empirical study and political concern. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Black body became a central site through which scientific racism was naturalised and institutionalised. Rather than treating race solely as a taxonomic abstraction, anthropologists and state officials began to treat the bodies of Black people as repositories of deviance—biological, moral, and civilisational (Baker 1998). These discourses were not merely academic; they helped legitimise the structural realities of post-emancipation Black life, including structural poverty, segregation, political exclusion, and the ever-present threat of rebellion. Within this context, the Black body was framed not just as different, but as existentially dangerous—a problem to be studied, managed, and contained.

In post-Emancipation America (1865–1955), this racialised scrutiny took the form of what policymakers and social scientists called the ‘negro problem’ (Baker 1998; Du Bois 1903; 1935). The presence of millions of recently emancipated people in a supposedly democratic society raised an urgent socio-political question: What to do with the Blacks? Integration? Segregation? Expulsion to Africa? In response, segregationist laws known as ‘Black codes’, Jim Crow laws, lynch mobs, and the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan’s terrorism reinforced racial domination through legal, social, and extra-legal means—perpetuating exclusion from education, labour, property, and political life (Davis et al. [1941] 2022; Du Bois 1935; Woodward 1955).

The so-called ‘negro problem’ was thus a cultural trope shaped by deep-rooted ‘negrophobia’—the psychic and social condition in which Black bodies become projections of white fear, guilt, and fantasy, and the enduring legacies of slavery and settler colonialism (Butler 1993; Du Bois 1903; Fanon 1952; Ralph and Chance 2014). Black bodies became overdetermined by contradictory myths and stereotypes: biologically inferior yet physically threatening, hypersexual yet degenerate, human yet animal. They were objectified as specimens for medical and anthropological study and symbolically constructed as social threats to white civility and national order. As Frantz Fanon (1952) and Winthrop Jordan (1968) note, Black people were positioned somewhere between human and beast—feared, surveilled, and exploited.

American popular and scientific literatures alike portrayed Black men as ‘savages’ with uncontrollable lust for white women (Baker 1998; Fanon 1952). The myth of the Black rapist served to justify lynchings and other extrajudicial forms of racial terror (Wells 1909; Davis 1981). The Black male body was pathologised as criminal, immoral, and uncivilised (Muhammad 2010). These narratives were reinforced by legal mechanisms such as ‘anti-miscegenation’ laws, which limited Black people’s rights to get married, the ‘one-drop rule’, which asserted that anyone with a Black ancestor should also be racialised as Black, and the criminalisation of poverty through vagrancy and loitering statutes—all of which enabled the de facto re-enslavement of Black people through the convict leasing system, through which prisons could lease the forced labour of mostly Black prisoners to wealthy individuals and corporations (Blackmon 2008; Oshinsky 1996).

The trope of the Black criminal normalised systemic anti-Blackness and legitimated mass incarceration as a form of racial governance (Jordan 2014; Muhammad 2010). Structural racism, predicated on anti-Blackness, displaced responsibility for Black suffering onto Black people themselves. Structural racism refers to the ways that institutions, policies, and social arrangements collectively produce and reproduce racial inequality. Eugenicists, for example, used demographic data on Black mortality to predict the supposed ‘extinction of the Negro’ by the twentieth century (Brandt 1978; Ralph 2012; Muhammad 2010). These morbid fantasies ignored the systemic conditions of racialised death and pathologised Black existence that persist until today (Dennis 1995; Mbembe 2019). For example, young Black and Latinx men in East Harlem, confronting systemic unemployment, are made to navigate illicit economies —such as the street-level drug trade and other informal survival strategies that emerge in response to exclusion from the formal labor market—while their bodies are surveilled, punished, or absorbed into carceral systems designed for profit maximization (Bourgois 2003).

The commodification of Black bodies has long underwritten the global capitalist economy, from the extraction of labour under slavery to contemporary racialised markets in entertainment, sports, surveillance, and incarceration. Numerous ethnographic studies have examined how Black bodies are treated as fungible assets—valued for their productivity, aesthetic, or capacity for violence, yet systematically devalued as persons. In the US, for instance, Black bodies are hyper-visible in popular media yet constrained by controlling images that reflect and reproduce racial hierarchies (Gray 1995; Jackson Jr. 2005). In popular culture, recurring stereotypes such as the ‘mammy’—the loyal, self-sacrificing domestic servant—and the ‘welfare queen’—depicted as lazy, hyper-fertile, and parasitic—serve to naturalise Black women's social subordination and rationalise structural inequality through familiar visual tropes (Collins 2000).

Even in the American healthcare system, Black patients are often treated as less-than-human within clinical settings, where capitalist logics and anti-Black racism intersect to devalue Black patients’ pain, experiences, and lives (Rouse 2009). These racialised medical encounters are shaped by ‘ethical variability’, whereby clinicians justify unequal care by invoking culturally biased notions of responsibility, credibility, and worthiness.

Afrophobia

‘Afrophobia’ refers to a deep-seated hatred and fear of anything associated with Blackness or Africanness. The concept is closely related to ‘negrophobia’, both emerging from long-standing European traditions of imagining African peoples as inferior, dangerous, disorderly, or contaminating. Its discursive roots trace to Greco-Roman and medieval European portrayals of Africans as monstrous and uncivilised (Stewart 2005, 43; Cantave 2024, 863). In the modern world, Afrophobia encompasses not only aesthetic prejudice but also a globalised fear of African peoples, cultural traditions, and their capacity to unsettle white supremacy and Euro-American hegemony. In Latin America, this manifests in the stigmatisation and criminalisation of African-derived spiritual traditions such as Santería in Cuba, Candomblé in Brazil, and Haitian Vodou (Beliso-De Jesús 2015). These traditions—born in the crucible of slavery and colonial violence—are not simply forms of worship but cultural systems of Black survival, resistance, and world-making (Boaz 2021; Stewart 2005; Cantave 2024).

Historically, anthropology was complicit in shaping Afrophobic knowledge regimes. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century ethnographers often depicted African spiritual practices as primitive ‘superstitions’, aligning with colonial regimes that sought to eradicate them. Classic ethnographies in French and Iberian colonies portrayed Vodou and Candomblé as irrational or pathological—reinforcing racist state policies. Early anthropological writing rarely took these belief systems seriously as coherent cosmologies, instead treating them as exotic curiosities or proof of Black primitivism (Brown 2003).

Yet anthropology has also helped challenge these frameworks. Contemporary Afro-diasporic ethnographers and critical anthropologists have reclaimed the study of African-derived religions as a site of political and epistemological contestation. In this vein, scholars have foregrounded how practitioners understand their own rituals as ethical, affective, and intellectual forms of life-making. They also show how gender, sexuality, and embodiment are transformed through spiritual practice (Pérez 2016; Daniel 2005; Tinsley 2008).

In the Dominican Republic, Afrophobia is materially enacted in everyday life—especially through racialised anxieties about beauty, hygiene, and spiritual purity (Candelario 2007). Dominican beauty salons serve as intimate spaces where Afro-Haitian features and aesthetics are policed and effaced. Here, Haitian migrants are stigmatised not only for their Blackness but for presumed associations with Vodou, often framed publicly as satanic or uncivilised. These anxieties are entangled with fears of national degeneration and cultural contamination. Ethnographic observations such as these show how the body becomes a moral frontier where race, nation, and spirit converge—and where Afrophobic violence is inscribed onto skin, hair, and comportment.

In this context, anthropological studies that centre the lived experiences of Afro-religious practitioners offer critical tools to decolonise knowledge and confront Afrophobia. They reveal African diasporic religions not as threats to national order but as vital repositories of historical memory, resilience, and political possibility. At their best, ethnographic methods can expose the micro-practices of racial domination while amplifying Black cultural life on its own terms.

Misogynoir and Black feminist anthropology

‘Misogynoir’ refers to the specific forms of violence and dehumanisation that Black women experience at the intersection of anti-Black racism and misogyny (Bailey 2021). Historically, Black women’s bodies were subjected to scientific, sexual, and symbolic violation. A paradigmatic example is Saartjie Baartman (c.1789–1815), a Khoi woman from South Africa exhibited in nineteenth-century Europe as the ‘Hottentot Venus’ (Gilman 1985; Magubane 2001; Strother 1999). Her semi-nude body was displayed to curious European audiences, and after her death, her remains were dissected by French anatomist Georges Cuvier and exhibited at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris until 1974. Baartman’s treatment exemplified how the Black female body was racialised, sexualised, and rendered a scientific object—central to the development of comparative anatomy and early anthropological inquiry.

Contemporary Black feminist anthropologists have shown how this colonial gaze continues to shape representations of Black women. They point out that Black women’s bodies have historically been ‘disciplined’ through contradictory social discourses—from Christian morality and motherhood to racist stereotypes of hypersexuality and labour, and that white and Black women are constructed in opposition to each other: white women as symbols of domestic virtue and Black women as oversexualised ‘workhorses’ (Shaw 2001). Consequently, Black women in postcolonial Zimbabwe, as well as the post–civil rights era in the United States, navigate persistent gendered-racial expectations, often by asserting alternative moral, religious, and familial frameworks to reclaim bodily autonomy and dignity (Shaw 2001).

Other ethnographic studies also reveal the complex ways Black women resist, negotiate, or internalise these intersecting oppressions. For instance, Afro-Caribbean girls in New York are simultaneously hyper-visible and invisible in public space—fetishised as style icons and simultaneously policed as disruptive. Their creative expressions through fashion, music, and dance are often criminalised, yet also serve as strategies of survival and identity (LaBennett 2011). Similarly, young Black women in a transitional housing shelter in Detroit use performance and expressive culture to resist the stigmatisation of Black girlhood (Cox 2015). These ethnographies illuminate the lived experience of misogynoir and demonstrate how Black women mobilise care, kinship, and creativity in the face of structural violence.

Importantly, Black feminist scholars have also highlighted the intra-racial dimensions of misogyny. Black women are often expected to subordinate their experiences of gendered violence to broader racial struggles, leading to silences around the harm they endure from Black men (Collins 2000; Combahee River Collective 1977; Crenshaw 2014; Davis 1981; Lorde 1984). Anthropologists have argued that ethnography is particularly well-suited to expose these overlapping systems of oppression by attending to the quotidian textures of abuse, labour, survival, and joy in Black women’s lives (Mullings 2005b; McClaurin 2001). Black feminist anthropologists aim to make Black women’s lives ‘both visible and audible’ (McClaurin 2001, 21), a political and methodological project that resists both invisibility as well as hyper-surveillance. Gertrude Fraser’s (1998) ethnographic research on Black midwifery and the racial politics of reproductive health exemplifies this approach. She shows how Black women’s bodies and labour are routinely devalued in clinical and institutional settings. Attending to the embodied and generational knowledge of Black women healthcare workers illuminates how racism, sexism, and professional hierarchies intersect to marginalise Black women’s authority and care work. By centring Black women’s voices, labour, and intellectual production, Black feminist anthropology challenges the discipline to reckon with its own racial and gendered hierarchies—and to imagine new possibilities for more ethical, inclusive, and liberatory knowledge-making (McClaurin 2001). Yet, despite these contributions, Black women anthropologists have historically been marginalised within the academy. Their scholarship remains under-cited and undervalued in disciplinary canons (Harrison et al. 2018; Smith 2021; Williams 2021). This epistemic exclusion reflects broader patterns of anti-Blackness and sexism that pervade the discipline of anthropology itself.

Racial capitalism

‘Racial capitalism’ refers to the process by which capitalist economies have always been structured by and dependent upon racial hierarchies and the exploitation of Black labour. First developed by Cedric Robinson (1983), the concept critiques the idea that capitalism is a racially neutral economic system only later corrupted by racism. Robinson argues that capitalism emerged from European feudal orders that already encoded racial difference, and that Black people have been subjected to a distinct form of economic subjugation central to the global capitalist order. In this view, anti-Blackness is not a by-product of capitalism but foundational to its formation and endurance (Du Bois 1935; Williams 1940; Robinson 1983; Matlon 2016).

Anthropologists have documented how Black life is shaped by systems of racialised accumulation and dispossession, from plantation slavery to contemporary neoliberalism. Insurance policies on enslaved Africans in the nineteenth century US South illustrate the fusion of racial logics and financial speculation (Ralph 2012). Enslaved people were rendered fungible labour and abstract instruments of credit and actuarial calculation. Their value derived not from their humanity but from their capacity to generate returns for owners and insurers. Slave insurance reveals how Black life was financialised in ways that shaped modern capitalism, including the development of life insurance, risk management, and governance of future value.

Historian Destin Jenkins (2021) builds on this understanding with a historical analysis of how municipal debt became a tool of racial governance in twentieth century San Francisco—a framework that offers important insights for anthropological approaches to racial capitalism. Drawing on archival research, Jenkins shows how bond markets and credit-rating agencies influenced public infrastructure decisions, disinvesting from Black neighbourhoods while underwriting white wealth accumulation. Racial capitalism thus operates not only through exploitation but through financial infrastructures that dictate whose futures are investable.

In the Caribbean, economic policies associated with globalisation, tourism, and austerity have likewise entrenched anti-Black hierarchies (Slocun 2006; Thomas 2019, 2021). In urban Jamaica, Black youth are simultaneously criminalised and commodified—as symbols of urban danger for tourists and as security laborers in the very industries that exclude them. In this way, Blackness is linked to economic disposability while also being monetised within global security regimes (Jaffe 2015).

Similarly, labour struggles in Guadeloupe are shaped by colonial legacies and racialised inequality, as Black workers mobilise both class and race to challenge French imperial domination (Bonilla 2021). Ethnographic research with rural St. Lucian women in the banana export industry also reveals the racialised and gendered dimensions of global capitalism (Slocum 2006). Here, Black women navigate the intersecting pressures of neoliberal trade regimes, postcolonial marginalisation, and local class hierarchies, and underscore how global capitalism reproduces racial and gendered inequalities. For example, many women farmers must absorb the risks of volatile export prices, perform the unpaid labour required to meet stringent quality standards, and contend with male intermediaries who control access to markets and resources, leaving them disproportionately vulnerable within global commodity chains.

Anthropologists working in the tradition of structural violence—a concept popularised by Paul Farmer (2004)—have shown how racialised violence is embedded in political and economic systems, not just individual attitudes. Structural violence refers to the historically produced social arrangements—such as poverty, segregation, and unequal access to healthcare—that systematically harm marginalised populations by constraining their life chances and exposing them to preventable suffering. While structural racism is a specific form of this violence, rooted in racial hierarchy and anti-Blackness, structural violence more broadly encompasses the multiple social forces that produce patterns of inequality and harm. Farmer’s work in Haiti traced how colonialism and neoliberalism shape health outcomes through institutional neglect and economic exploitation. Building on this, Adia Benton’s (2015) ethnography of Sierra Leone’s HIV response reveals how global health regimes reproduce racialised and gendered hierarchies, exposing whose lives are deemed valuable or not.

The Harlem Birth Right Project, led by Leith Mullings (2001; 2005b), further developed this approach in the US context, analysing how race, gender, and class intersect to produce structural vulnerability. Their research linked high rates of infant mortality among Black women in Harlem to housing insecurity, over-policing, and barriers to quality prenatal care. Other ethnographers have likewise shown how structural racism is embodied through cyclical poverty, over-policing, and healthcare inequality (Bourgois 1995; Scheper-Hughes 1992). Together, these studies reveal how anti-Blackness is infrastructural—woven into the built environment, labour markets, and social services—and how racial capitalism renders Black life both exploitable and expendable.

‘Colour-blindness’ and colourism

Anti-Blackness is a fact of everyday life across the postcolonial world (Fanon 1952; Essed and Goldberg 2002; Keaton 2023). Yet for much of the twentieth century, anthropology’s ability to study racism seriously was constrained by post-Boasian liberalism and its doctrinal commitments to anti-essentialism and ‘colour-blindness’ (Allen and Jobson 2016; Anderson 2019; Baker 1998; Mullings 2005a; Shanklin 1998). These liberal frameworks, dominant since the 1960s, often dismissed structural racism as a serious object of anthropological inquiry. As scholars have argued, late twentieth-century racial ideologies increasingly took the form of ‘colour-blind racism’ or ‘racism without races’—systems of inequality that deny the significance of race while reproducing its effects through ostensibly race-neutral institutions, discourses, and practices (Bangstad and Fuentes 2023; Bonilla-Silva 2015; Omi and Winant 1986). With the rise of Black Studies in the 1960s and 1970s, and the inclusion of more Black and Indigenous anthropologists, critical ethnographic research has increasingly foregrounded the structures and lived conditions of anti-Blackness—reshaping academic knowledge and the local-global politics of race.

Contemporary anthropology is especially well positioned to examine the overlapping and divergent manifestations of anti-Blackness worldwide. While unified by a global racialised formation, the expressions of anti-Blackness in Ghana, Brazil, the US, Haiti, Ethiopia, Jamaica, and Europe vary significantly, shaped by distinct colonial histories, nationalist projects, and local racial regimes (Jung and Vargas 2021, 2022; Mills 2021). Jamaica, for example, enjoys sovereignty without emancipation from US imperialism (Thomas 2019), while African Americans have experienced emancipation from slavery without sovereignty (Shange 2019, 8). These divergent trajectories shape distinct yet interconnected experiences of anti-Blackness which emerge from the afterlives of empire, revealing how racial domination is reproduced across multiple global sites (Thomas and Clarke 2013).

Anti-Blackness manifests through surveillance, discipline, and the differential valuation of Black life. Black people are routinely seen as threatening, unruly, or out of place (Browne 2015; Butler 1993; Sharpe 2016). These racialised perceptions give rise to punitive structures—both spectacular and mundane—that discipline Black bodies. In eighteenth century New York, for instance, Black, Indigenous, and mixed-race individuals were legally required to carry lanterns after dark to illuminate their faces (Browne 2015). Today, such logics persist in policing, education, and carceral systems. For example, in her study of a San Francisco school, Savannah Shange (2019) describes how Black and Latinx youth are disciplined through ‘carceral progressivism’, i.e. the use of multicultural rhetoric that claims to lament structural racism, but still insists on zero-tolerance and police-based approaches to disciplining Black people and justify racial control. In Australia, Aboriginal youth are incarcerated at 20 times the rate of their white peers, revealing how settler colonialism continues to target Black and Indigenous life under the banner of multiculturalism (Holland et al. 2024; Hage 2000; Povinelli 2002; Wolfe 2016).

Ethnographies in the Caribbean and Latin America show how anti-Blackness animates postcolonial statecraft and global capitalism. In Jamaica, American militarism and neoliberalism have shaped violent policing regimes (Thomas 2019) while in Brazil, anthropologists have documented how militarised policing specifically targets Black favelas (Alves 2018; Smith 2016; Gillam 2022). Perhaps the most striking example comes from Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, a place that is marketed as an ‘Afro-paradise’—a transnational fantasy that celebrates Afro-Brazilian culture for tourism and national identity—even as the state continues to subject Black communities to pervasive violence and surveillance. Indeed, Black communities have long been sites of routinised, yet spectacular, racialised violence (Smith 2016). Here, Afro-Brazilians resist anti-Blackness through protest and performance practices—particularly bloco afro processions, Carnival-based counter-performances, and community mobilisations against police violence—in everyday life.

In the US, Laurence Ralph (2020) shows how the Chicago Police Department systematised torture against Black men from the 1970s to 1990s. In Detroit, Aimee Cox (2016) details how unhoused Black girls choreograph strategic movements through hostile urban spaces to claim dignity and survival. These ‘choreographies’ are not only acts of endurance but also everyday refusals of disposability. Together, these ethnographies show that anti-Blackness is not limited to spectacular violence but is embedded in quotidian institutions that constrain and surveil Black life. Anthropology, when critically engaged, offers tools to document these dynamics and to amplify Black knowledge, resistance, and worldmaking.

‘Colourism’ is another important facet of anti-Blackness. It refers to prejudice and discrimination based on skin tone, often within Black and Brown communities (Glenn 2009; Jablonski 2021). Coined by Alice Walker (1983), ‘colourism’ names the global preference for lighter skin in proximity to whiteness (Bajwa et al. 2023). People experience it daily: in family life, dating, beauty, housing, healthcare, education, media, and policing (Caldwell 2007; Anekwe 2014; Monk 2015; Spears 2020). Though the term is modern, colourism is centuries old, shaped by slavery, colonialism, and racial science. In colonial Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), French jurist Moreau de Saint-Méry (1796) identified eleven gradations of racial mixture, praising the ‘mulatto’ as the ideal hybrid. He wrote:

Of all the combination of white and nègre it is the mulatto who brings together all of the physical advantages; of all of these crossings of race he is the one who has the strongest constitution, the most appropriate to Saint-Domingue's climate. To the sobriety and the strength of the nègre he joins the physical grace and the intelligence of the white (1798; Garrigus 2006).

Such fantasies fused early scientific racism with erotic desire, projecting European superiority onto the bodies of the enslaved. As many scholars have argued, early racial science was animated by anxieties over miscegenation, bodily purity, and racial control (Fanon 1954; Jordan 1968; Stoler 2002; Wolfe 2016). Moreover, ‘racially hierarchical social orders, which are rooted in the control and exploitation of (racially identified) peoples and places […] generate complex dynamics of hate and love, fear and fascination, contempt and admiration […] that seems to have a specifically sexual dimension’ (Wade 2009, 2).

Colourism is historically and geographically contingent. In the US, the ‘one-drop rule’ collapsed racial ambiguity into a rigid Black-white binary (Hochschild and Powell 2008; Jordan 2014). Yet lighter-skinned Black people—particularly women—have often been granted greater social capital and proximity to whiteness (Larsen 1929; Walker 1983). In South Africa, Haiti, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico, ‘pigmentocracies’ used gradations of skin tone to structure social life (Bacelar da Silva 2022; Jackson 2024; Sheriff 2001; Telles 2014). Terms like ‘coloured’, ‘milat’, ‘mulato’, and ‘mestizo’ mark intermediate racial categories, creating buffer classes that were closer to whiteness but denied its full privileges (Glenn 2009). This stratification fostered internalised racism and horizontal antagonisms (Spears 2020; Walker 1983).

Ethnographic research shows that in Latin America, racial identities are often expressed through skin tone rather than fixed categories, and are shaped by context, class position, and local understandings of ancestry. As Peter Wade (2009) notes, racial classification in the region is fluid, relational, and embedded in broader national ideologies of mestizaje that link colour, class, and sexuality. In many settings, individuals may be identified differently depending on region, social status, or interpersonal interactions. In Mexico, descriptors like ‘moreno’ or ‘güero’ serve as racial signifiers that shift with context (Sue 2013). In Brazil, ideologies of ‘racial democracy’ have long obscured structural inequalities perpetuated by anti-Blackness and colourism (Hordge-Freeman 2015; Sheriff 2001; Twine 1998). In the Dominican Republic, anti-Haitianism reinforces the association of Blackness with cultural and national undesirability (Aber and Small 2013; Candelario 2007).

Skin bleaching is a global phenomenon, not confined to Black Atlantic societies. In India, the Philippines, South Korea, Peru, and Ghana, lighter skin is linked with beauty and modernity (Glenn 2009; Jha 2015; Mishra 2015; Pierre 2015). Many products contain mercury, hydroquinone, or potent topical steroids, causing severe dermatological damage—including chemical burns, skin thinning, and ochronosis—as well as systemic risks such as kidney failure, hypertension, and neurological toxicity. Despite these severe health risks, the global skin-lightening industry exceeds $8 billion annually and is expected to continue growing.

Colourism reveals that anti-Blackness cuts across national borders and ‘people of colour’ (‘POC’) categories. Although the term ‘POC’ is often mobilised to foster cross-ethnic alliances and highlight shared experiences of marginalisation, the term can also flatten important differences by subsuming distinct racial histories under a single label. In particular, it can obscure the structural and quotidian nature of anti-Blackness, diluting attention to the specific forms of violence, exclusion, and state surveillance directed at Black communities.

This points to the fact that anti-Blackness is not just a legacy of colonialism—it is a structuring logic of the modern racial order (Vargas 2018). Everyday manifestations of anti-Blackness, whether through skin tone, surveillance, or institutional neglect, underscore the systemic nature of racial violence. Anthropology, at its best, offers the methodological tools to document and disrupt these patterns.

Conclusion

Anthropology has long been complicit in the perpetuation of anti-Blackness and white supremacy, at times functioning as a tool of racial domination and colonial conquest (Beliso-De Jesús, Pierre and Rana 2025; Gupta and Stoolman 2021; Mullings 2005a). Yet anthropology also holds liberatory potential, precisely because it seeks to understand how social structures and relations, political hierarchies, and hegemonic cultures are experienced by people themselves (Harrison 1991; Cox et al. 2022; Mullings 2005a). By engaging with theories of anti-Blackness—especially those developed beyond the discipline—anthropology can interrogate its own historical complicity while contributing to contemporary Black freedom struggles worldwide.

The Movement for Black Lives—a global social movement against the ongoing structural devaluation of Black life and the resurgence of white nationalist politics—underscores the urgency of this task (Beliso-De Jesús, Pierre and Rana 2025; Jung and Vargas 2021; Williams 2015). From anti-police violence protests in the US to anti-racist demonstrations abroad, this movement highlights both the persistence of racial violence and the resilience of Black communities.[5] Anthropological perspectives are essential here—not only to bear witness to how Black people experience and endure anti-Blackness, but also to illuminate how they resist and reimagine these structures in everyday life.

Black feminist anthropologists have long shown that centring Black humanity requires analysing intersecting oppressions and committing to politically engaged scholarship in Black communities themselves (Bolles 2001; Harrison 1991; McClaurin 2001). Despite this, Black women anthropologists have themselves been marginalised or excluded from the discipline’s canon, and their work remains undervalued (Harrison et al. 2018; McClaurin 2001; Smith 2021; Williams 2021). This epistemic erasure not only marginalises scholars but also silences the communities they represent. It exposes how dominant notions of merit and rigor remain shaped by Eurocentric, anti-Black, and sexist assumptions (McClaurin 2001). In response, Black feminist anthropologists continue to counter this devaluation by making Black women’s lives and voices ‘both visible and audible’ (McClaurin 2001, 21).

Calls for abolitionist anthropology, informed by the Movement for Black Lives, remind us that the discipline must embrace more liberatory frameworks for representing human experience (Cox et al. 2022; Harrison 1991). Black practices of fugitivity, marronage—historically, the flight of enslaved people who formed autonomous communities in resistance to colonial domination—storytelling, witness-bearing, and radical ‘freedom dreams’ envision life beyond the ubiquitous ‘weather’ of anti-Blackness. These visions are grounded in the lived realities and cultural imaginaries of Black people (Allen and Jobson 2016; Kelley 2002; Sharpe 2016). To remain relevant to the critical study of the human condition, anthropology must treat anti-Blackness not as peripheral, but as foundational to understanding the modern world (Jung and Vargas 2021; Wilderson 2003). In this way, anthropology can not only interrogate its own colonial legacies, but also serve as a tool for amplifying the voices, experiences, and aspirations of Black communities globally, contributing to the broader struggle for racial justice.

References

Allen, Jafari S., and Ryan C. Jobson. 2016. “The decolonizing generation: (Race and) theory in anthropology since the eighties.” Current Anthropology 104, no. 3: 783–90.

Alves, Jaime A. 2018. The anti-Black city: Police terror and Black urban life in Brazil. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Anderson, Mark. 2019. From Boas to Black Power: Racism, liberalism, and American anthropology. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Anjari, Simran. 2022. “From Black consciousness to Black Lives Matter: Confronting the colonial legacy of colourism in South Africa.” Agenda: Empowering Women in Gender Equity 36, no. 4: 158–69.

Bacelar da Silva, Antonio J. 2022. Between Brown and Black: Anti-racist activism in Brazil. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Bailey, Moya. 2021. Misogynoir transformed: Black women’s digital resistance. New York: NYU Press.

Bajwa, Marium, Imke von Maur, and Achim Stephan. 2023. “Colorism in the Indian Subcontinent: Insights through situated affectivity.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences (online). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-023-09901-6

Baker, Lee D. 1998. From savage to Negro: Anthropology and the construction of race, 1896-1954. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

–––––––. 2020. “The racist anti-racism of American anthropology.” Transforming Anthropology 290, no. 2: 127–42.

Baldwin, James, and Margaret Mead. 1971. A rap on race. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott.

Beliso-De Jesús, Aisha. 2015. Electric santería: Racial and sexual assemblages of transnational religion. New York: Columbia University Press.

Beliso-De Jesús, Aisha, Jemima Pierre, and Junaid Rana. 2025. The anthropology of white supremacy: A reader. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Benton, Adia. 2015. HIV exceptionalism: Development through disease in Sierra Leone. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bindman, David, and Henry Louis Gates Jr., eds. 2010. The image of the Black in Western art, vol. 2: From the early Christian era to the "Age of Discovery." Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Blackmon, Douglas A. 2008. Slavery by another name: The re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. London: Icon Books.

Blakey, Michael L. 2010. “Man and nature, white and other.” In Decolonizing anthropology: Moving further toward an anthropology of liberation. Third edition. Edited by Faye Harrison, 16–24. Arlington: American Anthropological Association.

–––––––. 2020. “Archaeology under the blinding light of race.” Current Anthropology 61, no. 22: S183–97.

Blumenbach, Johann F. 1865. The anthropological treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. Edited and translated by Thomas Bendyshe. London: The Anthropological Society.

Boaz, Danielle N. 2021. Banning the Black gods: Law and religions of the African diaspora. University Park: The Pennsylvania University State Press.

Bolles, Lynn A. 2001. “Theorizing a Black feminist self in anthropology: Toward an autobiographic approach.” In Black feminist anthropology: Theory, politics, praxis, and poetics. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Bonilla, Yarimar. 2015. Non-sovereign futures: French Caribbean politics in the wake of disenchantment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2015. “The structure of racism in color-blind, ‘post-racial’ America.” American Behavioral Scientist 59, no. 11: 1358–76.

Bourgois, Philippe. 1995. In search of respect: Selling crack in El Barrio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brandt, Allan. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.” The Hastings Center Report 8, no. 6: 21–9.

Brodkin, Karen, Sandra Morgen, and Janis Hutchinson. 2011. “Anthropology as white public space?” American Anthropologist 113, no. 4: 545–56.

Brown, Jaqueline Nassy. 1998. “Black Liverpool, Black America, and the gendering of diasporic space.” Cultural Anthropology 13, no. 3: 291–325.

Browne, Simone. 2015. Dark matters: On the surveillance of Blackness. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Butler, Judith. 1993. “Endangered/endangering: Schematic racism and white paranoia.” In Reading Rodney King/Reading urban uprising, edited by Robert Gooding-Williams, 16–23. New York: Routledge.

Candelario, Ginetta E.B. 2007. Black behind the ears: Dominican racial identity from museums to beauty shops. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Cantave, Rachel. 2024. “Pursuing racial order and social progress: Violence, Afrophobia and ‘religious racism’ in Brazil.” Latin American Research Review 59, no. 4: 858–71.

Chamberlain, Alexander. 1907. “Thomas Jefferson’s ethnological opinions and activities.” American Anthropologist 9, no. 3: 499–509.

Cohen, William. 1969. “Thomas Jefferson and the problem of slavery.” Journal of American History 56, no. 1: 503–26.

Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Second edition. New York: Routledge.

Combahee River Collective. (1977) 2017. “The Combahee River Collective Statement.” In How we get free: In Black feminism and the Combahee River Collective, edited by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, 15–27. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Cox, Aimee M. 2015. Shapeshifters: Black girls and the choreography of citizenship. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Cox, Aimee, Savannah Shange, Christen Smith, and Deborah Thomas. “An anthropology of abolition/liberation with Aimee M. Cox and panelists.” Yale University. April 6, 2022. YouTube video, 28:51. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-BTMpj9KYI&t=1731s.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 2014. On intersectionality: Essential writings. New York: The New Press.

Davis, Allison, Burleigh Gardner, and Mary Gardner. (1941) 2022. Deep South: A social anthropological study of caste and class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Davis, Angela. 1981. Women, race and class. New York: Random House.

Dennis, Rutledge. 1995. “Social Darwinism, scientific racism, and the metaphysics of race.” The Journal of Negro Education 64, no. 3: 243–52.

Drake, St. Clair, and Willie Baber. 1990. “Further reflections on anthropology and the Black experience.” Transforming Anthropology 1, no. 2: 1–14.

Douglass, Frederick. (1881) 2022. “The color line.” In Douglass: Speeches and writings. New York: Library of America.

–––––––. 1854. The claims of the Negro, ethnologically considered. Rochester, N.Y.: Lee, Mann & Co.

Drake, St. Clair, and Horace R. Cayton. 1945. Black metropolis: A study of Negro life in a northern city. New York: Harper & Row.

Du Bois, W.E.B. (1903) 1996. The souls of Black folk. New York: Penguin Books.

–––––––. (1935) 1998. Black reconstruction in America, 1860-1880. New York: The Free Press.

DuVernay, Ava. 2016. 13th. Netflix. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=krfcq5pF8u8.

Essed, Philomena. 1991. Understanding everyday racism: An interdisciplinary theory. London: Sage Press.

Essed, Philomena, and David T. Goldberg, eds. 2002. Race critical theories: Text and context. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell.

Eze, Emmanuel C. 1997. Race and the Enlightenment: A reader. Oxford: Blackwell.

Fabian, Johannes. (1983) 2014. Time and the other: How anthropology makes its objects. New York: Columbia University Press.

Fanon, Frantz. (1952) 2008. Black skin, white masks. Translated by Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press.

Farmer, Paul. 2004. "An anthropology of structural violence." Current Anthropology 45, no. 3: 305–25.

Finkelman, Paul. 2014. Slavery and the founders: Race and liberty in the age of Jefferson. Third edition. London: Routledge.

Firmin, Anténor. (1885) 2000. The equality of the human races (positivist anthropology). Translated by Asselin Charles. New York: Garland Publishing Inc.

Fleur-Lobban, Carolyn. 2000. “Anténor Firmin: Haitian pioneer of anthropology.” American Anthropologist 102, no. 3: 449–66.

Franklin, John Hope. 1989. Race and history: Selected essays, 1938-1988. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Fraser, Gertrude J. 1998. African American midwifery in the South: Dialogues of birth, race, and memory. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Garraway, Doris. 2005. “Race, reproduction and family romance in Moreau de Saint-Méry’s Description […] de la partie française de l’Isle Saint-Domingue.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 2: 227–46.

Garrigus, John D. 2006. Before Haiti: Race and citizenship in French Saint-Domingue. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., and Andrew Curran, eds. 2022. Who’s Black and why? A hidden chapter from the eighteenth-century invention of race. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

Gibson-Light, Michael. 2023. Orange-collar labour: Work and inequality in prison. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gillam, Reighan. 2022. Visualizing Black lives: Ownership and control in Afro-Brazilian media. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Gilman, Sander. 1985. “Black bodies, white bodies: Toward an iconography of female sexuality in late nineteenth-century art, medicine, and literature. Critical Inquiry 12, no. 1: 204–42.

Gilroy, Paul. 1987. ‘There ain’t no Black in the Union Jack’: The cultural politics of race and nation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

–––––––. 1993. The Black Atlantic modernity and double consciousness. London: Verso.

Glenn, Evelyn Nakano, ed. 2009. Shades of difference: Why skin color matters. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gray, Herman. 1995. Watching race: Television and the struggle for "Blackness". Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gupta, Akhil, and Jesie Stoolman. 2022. “Decolonizing US anthropology.” American Anthropologist 124: 778–99.

Hage, Ghassan. 2000. White nation: Fantasies of white supremacy in a multicultural society. New York: Routledge.

Hall, Stuart. (1997) 2013. “The spectacle of the ‘other.’” In Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Second edition. Edited by Stuart Hall, Jessica Evans, and Sean Nixon, 215–87. London: SAGE.

Harrison, Faye V. 1992. “The Du Boisian legacy in anthropology.” Critique of Anthropology 12, no. 3: 239–60.

–––––––. ed. (1991) 2010. Decolonizing anthropology: Moving further toward an anthropology for liberation. Third edition. Arlington: American Anthropological Association.

Harrison, Ira E., Deborah Johnson-Simon, and Erica Lorraine Williams, eds. 2018. The second generation of African American pioneers in anthropology. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Hartman, Saidiya. 1997. Scenes of subjection: Terror, slavery, and self-making in the nineteenth-century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Heath, Elizabeth. 2010. “Berlin Conference of 1884-1885.” In Encyclopedia of Africa, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Kwame Anthony Appiah. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780195337709.001.0001/acref-9780195337709-e-0467.

Hegel, G.W.F. (1837) 1894. Lectures on the history of philosophy. Translated by J. Sibree. London: George Bell & Sons.

Hochschild, Adam. 1998. King Leopold’s ghost: A story of greed, terror, and heroism in colonial Africa. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Hochschild, Jennifer L., and Brenna M. Powell. 2008. “Racial reorganization and the United States Census 1850-1930: Mulattoes, half-breeds, mixed parentage, Hindoos, and the Mexican race.” Studies in American Political Development 22: 59–96.

Holland, Lorelle, Claudia Lee, Maree Toombs, Andrew Smirnov, and Natasha Reid. 2024. First Nations Health and Wellbeing – The Lowitja Journal 2: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fnhli.2024.100023

Hordge-Freeman, Elizabeth. 2015. The color of love: Racial features, stigma, and the socialization in Black Brazilian families. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Hume, David. (1748) 1997. “Of national characters.” In Race and the Enlightenment: A reader, edited by Emmanuel C. Eze, 30–3. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hurston, Zora Neale. 1928. “How it feels to be colored me.” The World Tomorrow 11, no. 5: 215–6.

–––––––. 2018. Barracoon: The story of the last “Black cargo.” New York: HarperCollins.

Jablonski, Nina. 2021. “Skin color and race.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 175, no. 2: 437–47.

Jackson, John L., Jr. 2005. Real Black: Adventures in racial sincerity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jackson, Sebastian. 2024. “Miscegenation madness: Interracial intimacy and the politics of ‘purity’ in twentieth century South Africa.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research in Race 21, no. 2: 223–49.

Jaffe, Rivke. 2013. “The hybrid state: Crime and citizenship in urban Jamaica.” American Ethnologist 40, no. 4: 734–48.

James, C.L.R. 1938. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. London: Secker & Warburg.

–––––––. (1781) 2022. Notes on the state of Virginia. Edited by Robert Pierce Forbes. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Jenkins, Destin. 2021. The bonds of inequality: Debt and the making of the American city. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jha, Meeta. 2015. The global beauty industry: Colorism, racism, and the national body. First edition. New York: Routledge.

Johnson, Marguerite, and Alistair Rolls. 2023. “Georges Cuvier’s autopsy report on Sara Baartman: A translation and commentary.” Terrae Incognitae 55, no. 2: 170–95.

Jones, Delmos. 1970. “Towards a Native anthropology.” Human Organization 29, no. 4: 251–9.

Jordan, Winthrop. 1968. White over Black: American attitudes toward the Negro, 1550-1812. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

–––––––. 2014. “Historical origins of the one-drop racial rule in the United States.” Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies 1, no.1: 98–132.

Joseph, Daniel, and Bertin M. Louis Jr. 2022. “Anti-Haitianism and statelessness in the Caribbean.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 27, no. 3: 386-407.

Jung, Moon-Kie ,and João H. Costa Vargas, eds. 2021. Antiblackness. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Kant, Immanuel. (1764) 1997. “On national characteristics, so far as they depend upon the distinct feeling of the beautiful and sublime.” In Race and the Enlightenment: A reader, edited by Emmanuel C. Eze, 49–57. Oxford: Blackwell.

Keaton, Trica. 2023. #You know you’re Black in France when…: The fact of everyday antiblackness. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Keel, Terence. 2013. “From Africans to Negroes: Anthropology and the politics of racial science in the nineteenth century.” History of the Human Sciences 26, no. 1: 3–32

Larsen, Nella. 1929. Passing. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Lewis, Diane. 1973. “Anthropology and colonialism.” Current Anthropology 14, no. 5: 581–602.

Lindfors, Bernth, ed. 1999. Africans on stage: Studies in ethnological show business. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

von Linnaeus, Carl. (1735) 1997. “The God-given order of nature.” In Race and the Enlightenment: A reader, edited by Emmanuel C. Eze, 10–14. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lorde, Audre. 1984. Sister outsider. Trumansburg, N.Y.: The Crossing Press.

Magubane, Zine. 2001. “Which bodies matter? Feminism, poststructuralism, race and the curious theoretical odyssey of the ‘Hottentot Venus’.” Gender and Society 15, no. 6: 816–34.

–––––––. 2003. “Simians, savages, skulls, and sex: Science and colonial militarism in nineteenth-century South Africa.” In Race, nature and the politics of difference, edited by Donald Moore, Jake Kosek, and Anand Pandian, 99–121. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Matlon, Jordanna. 2016. “Racial capitalism and the crisis of Black masculinity.” American Sociological Review 81, no. 5: 1014–38.

Mbembe, Achille. 2019. Necropolitics. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

McClaurin, Irma, ed. 2001. Black feminist anthropology: Theory, politics, praxis, and poetics. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Mills, Charles W. 2021. “The illumination of Blackness.” In Antiblackness, edited by Moon-Kie Jung and João Costa Vargas, 17–36. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Mishra, N. 2015. “India and colorism: The finer nuances.” Washington University Global Studies Law Review 4, no. 14: 725–50.

Mondesire, Zachary. 2022. “A Black exit interview from anthropology.” American Anthropologist 124, no.3: 613–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13755

Monk, Ellis P., Jr. 2015. “The cost of color: Skin color, discrimination, and health among African Americans.” American Journal of Sociology 121, no.2: 396–444.

Moreau de Saint-Méry, M.L.E. 1798. Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de L'Isle Saint-Domingue, vol. 1 (Paris: Dupont). https://archive.org/details/descriptiontopog00more/page/n9/mode/2up

Morgan, Marcyliena. 2002. Language, discourse and power in African American culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morton, Samuel George. 1839. Crania Americana; or, a comparative view of the skulls of various Aboriginal Nations of North and South America: To which is prefixed an essay on the varieties of the human species. Philadelphia: J. Dobson.

Moton, Fred. 2008. “The case of Blackness.” Criticism 50, no. 2: 177–218.

Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. 2010. The condemnation of Blackness: Race, crime, and the making of modern urban America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Mullings, Leith. 2005a. “Interrogating racism: Toward an antiracist anthropology.” Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 667–93.

–––––––. 2005b. “Resistance and resilience: The Sojourner syndrome and the legacy of Black women’s health issues in the United States.” In Health and social justice: Politics, ideology, and inequity in the distribution of disease, edited by Richard Hofrichter, 345–68. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mullings, Leith, Alaka Wali, Diane McLean, Janet Mitchell, Sabiyha Prince, Deborah Thomas, and Patricia Tovar. 2001. “Qualitative methodologies and community participation in examining reproductive experiences: The Harlem Birth Right Project.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 5, no. 1: 85–93.

Nobles, Melissa. 2000. Shades of citizenship: Race and the census in modern politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Nott, Josiah C. 1843. “The mulatto a hybrid – probable extermination of the two races if the Whites and Blacks are allowed to intermarry.” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 29, no. 2: 29–32.

Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 1986. Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1980s. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Oshinsky, David M. 1996. “Worse than slavery”: Parchman Farm and the ordeal of Jim Crow justice. New York: Free Press.

Painter, Nell I. 2010. The history of white people. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Pascoe, Peggy. 2009. What comes naturally: Miscegenation law and the making of race in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Patterson, Orlando. 1982. Slavery and social death. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Perkins, Rachel, and Marcia Langton. 2008. First Australians: An illustrated history. Melbourne: Miegunyah Press.

Perry, Keisha-Khan Y. 2013. Black women against the land grab: The fight for racial justice in Brazil. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Pierre, Jemima. 2013. The predicament of Blackness: Postcolonial Ghana and the politics of race. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

–––––––. 2020. “Slavery, anthropological knowledge, and the racialization of Africans.” Current Anthropology 21, no.22: s220–31.

Povinelli, Elizabeth. 2002. The cunning of recognition: Indigenous alterities and the making of Australian multiculturalism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Ralph, Laurence. 2020. The torture letters: Reckoning with police violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ralph, Laurence, and Kerry Chance. 2014. “Legacies of fear: From Rodney King’s beating to Trayvon Martin’s death.” Transition 133: 137–43.

Ralph, Michael. 2012. “‘Life…in the midst of death: ‘Notes on the relationship between slave insurance, life insurance and disability.” Disability Studies Quarterly 32, no. 3. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v32i3.3267

Robinson, Cedric. 1983. Black Marxism: The making of the Black radical tradition. London: Zedd Press.

Rodney, Walter. (1972) 2018. How Europe underdeveloped Africa. London: Verso.

Rodriguez, Cheryl. 2001. “A homegirl goes home: Black feminism and the lure of native anthropology.” In Black feminist anthropology: Theory, politics, praxis, and poetics, edited by Irma McClaurin, 233–58. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Rouse, Carolyn. 2009. Uncertain suffering: Racial health care disparities and sickle cell disease. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy. 1992. Death without weeping: The violence of everyday life in Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Scott, David. 2004. Conscripts of modernity: The tragedy of colonial Enlightenment. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

–––––––. 2014. “The theory of Haiti: The Black Jacobins and the poetics of universal history. Small Axe 18, no. 3: 35–51.

Sexton, Jared. 2008. Amalgamation schemes: Antiblackness and the critique of multiculturalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Shange, Savannah. 2019. Progressive dystopia: Abolition, antiblackness, and schooling in San Francisco. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Shanklin, Eugenia. 1999. “The profession of the color blind: sociocultural anthropology and racism in the 21st century.” American Anthropologist 100, no. 3: 669–79.

Sharpe, Christina. 2016. In the wake: On Blackness and being. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Shaw, Carolyn M. 2001. “Disciplining the Black female body: Learning feminism in Africa and the United States.” In Black feminist anthropology: Theory, politics, praxis, and poetics, edited by Irma McClaurin, 102–25. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Sheriff, Robin, E. 2001. Dreaming equality: Color, race, and racism in urban Brazil. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Slocum, Karla. 2006. Free trade and freedom: Neoliberalism, place, and nation in the Caribbean. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Smedley, Audrey. 1998. “‘Race’ and the construction of human identity.” American Anthropologist 100, no. 3: 690–702.

–––––––. (1993) 2007. Race in North America: Origin and evolution of a worldview. Third edition. Boulder, Co: Westview Press.

Smith, Christen A. 2016. Afro-paradise: Blackness, violence, and performance in Brazil. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

–––––––. 2021. “An introduction to Cite Black Women.” Feminist Anthropology 2, no. 1: 6–9.

Snowden, Frank. 1970. Blacks in antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman experience. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Spears, Arthur. 2020. “Racism, colorism, and language within their macro contexts.” In The Oxford handbook of language and race, edited by H.S. Alim, A. Reyes, and P. Kroskrity, 47–76. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

–––––––. 2021. “White supremacy and antiblackness: Theory and lived experience.” Linguistic Anthropology 31, no.2: 157–79.

Stewart, Dianne M. 2005. Three eyes for the journey: African dimensions of the Jamaican religious experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2002. Carnal knowledge and imperial power: Race and the intimate in colonial rule. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stoler, Ann Laura, ed. 2006. Haunted by empire: Geographies of intimacy in North American history. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Strother, Z.S. 1999. “Display of the body Hottentot.” In Africans on stage: Studies in ethnological show business, edited by Bernth Lindfors, 1–61. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sue, Christina A. 2013. Land of the cosmic race: Race mixture, racism, and Blackness in Mexico. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, Paul M., and Cesare Marino. 2019. “Paolo Mantegazza’s vision: The science of man behind the world’s first museum of anthropology (Florence, Italy, 1869).” Museum Anthropology 42, no. 2: 109–24.

Telles, Edward, ed. 2014. Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, race, and color in Latin America. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press.

Thomas, Deborah A. 2019. Political life in the wake of the plantation: Sovereignty, witnessing, repair. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Thomas, Deborah, and M. Kamari Clarke. 2013. “Globalization and race: Structures of inequality, new sovereignties, and citizenship in a neoliberal era.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 305–25.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1991. “Anthropology and the savage slot: The poetics and politics of otherness.” In Recapturing anthropology: Working in the present, edited by Richard G. Fox, 17–44. Santa Fe: University of New Mexico Press.

–––––––. 1995. Silencing the past: Power and the production of history. Boston: Beacon Press.

Twine, France Winddance. 1998. Racism in a racial democracy: The maintenance of white supremacy in Brazil. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Vargas, João H. Costa. 2018. The denial of antiblackness: Multiracial redemption and Black suffering. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wade, Peter. 2009. Race and sex in Latin America. New York: Pluto Press.

Walker, Alice. 1983. In search of our mother’s gardens: Womanist prose. San Diego: Harcourt.

Walker, David. 1830. David Walker’s appeal, in four articles; Together with a preamble, to the colored citizens of the world. Boston: D. Walker.

Weheliye, Alexander G. 2014. Habeas viscus: Racializing assemblages, biopolitics, and Black feminist theories of the human. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Wekker, Gloria. 2016. White innocence: Paradoxes of colonialism and race. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

West, Cornel. 2002. “A genealogy of modern racism.” In Race critical theories, edited by Philomena Essed and David Theo Goldberg, ____. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell.

Wilderson, Frank., III. 2020. Afropessimism. New York: Liveright.

Williams, Bianca C. 2015. “Introduction: #BlackLivesMatter.” Fieldsights: Theorizing the Contemporary, June 29. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/introduction-black-lives-matter.

Williams, Eric. (1944) 1994. Capitalism and slavery. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press.

Williams, Erica L. 2021. “Black girl abroad: An autoethnography of travel and the need to cite Black women in anthropology.” Feminist Anthropology 2, no. 1: 143–54.

Willis, William S., Jr. 1972. “Skeletons in the anthropological closet.” In Reinventing anthropology, edited by Dell Hymes, 121–52. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Wolf, Eric. 1982. Europe and the people without history. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2016. Traces of history: Elementary structures of race. London: Verso.